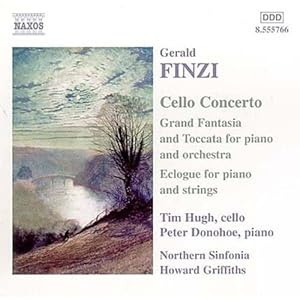

Gerald Finzi was the first composer whose entire oeuvre I loved. Some composers just speak to the core of your being, every note resonates, and seems to sing to your soul. Later I discovered other soul mates: Ives, Barber, Janacek, Goldschmidt, Crawford Seeger, Schoeck and others, but Finzi was the first. In fact he was the composer who is responsible for my unquenchable thirst and passion for classical music. And it all started with his cello concerto which I first heard aged 15 on a Naxos recording by Tim Hugh:

I was staggered at the beauty of this work - it was a feeling of finally finding the music that I had been yearning to hear (I had a similar experience a couple of years later when I first heard Strauss' Four Last Songs). This is the performance to get of this work - powerful, passionate, deeply poetic, completely outclassing the turgid and by comparison sentimentalised and bombastic Wallfisch account on Chandos, or even the youthful Yo-Yo Ma on Lyrita. For a while my line was that this was an English cello concerto greater than Elgar's (I don't think this anymore, but it certainly gives that warhorse a run for its money, and I'd prefer to hear the Finzi any day!) and I thought if music as wonderful as this was so woefully neglected, then what other beauties laid uncovered?

After this major discovery, I quickly devoured the rest of his output, and to my delight it yielded similar delights. Ubiquitous is the hushed and understated beauty, an aching sense of nostalgia, and occasional visionary moments of ecstatic soaring before they subside into soft toned poetry again. The chief influences are his musical heroes - Parry and Vaughan Williams for the pastoral, with Walton for spice, and Bach, the honorary Englishman as a model of uncluttered, economical lyricism and true sentiment (not to mention counterpoint).

The limitations are obvious: lack of technique to sustain the ideas, little feel for conventional tonal relationships and form, a severe lack of range, inability to write extended periods of fast music. And a little later when I discovered the sophistications of the contemporaneous avant-guarde - early Messiaen, Berg, Schoenberg, Bartok - his music seems naive and poorly made in the minds ear... but then you listen again and all these doubts disappear, beautiful phrase following beautiful phrase, all sounding so natural and heart-felt, honest and that it couldn't have been done any other way. Finzi's music is similar in effect, if not technique, (and certainly not skill) to Fauré's: soft hued, lyrical, melancholic works of calm, unearthly beauty.

The basic speed of his music is Andante-Adagio, and this speed naturally arises from, and gives rise to his normal approach to word setting - syllabic, with plodding, ruminating accompaniments, the poetry being matched note for note with the most apt and true tones that Finzi can muster. In the purely instrumental works too, the Adagio predominates - the abandoned projects mostly stuttered to a halt after the writing of the slow movement - thus we have the violin Elegy (1940), rather than a violin sonata, the piano Eclogue rather than a concerto, a slow Introit as the only officially recognised movement of an early violin concerto (1925), a slow Prelude for strings (1920s) and a Romance (1928) from a projected chamber symphony, a slowish and not terribly successful Interlude for oboe and strings, rather than a multi movement oboe quintet. The early Severn Rhapsody (1923) and Nocturne (1926) are also both slow. There are characteristic "Finzi phrases" that keep reappearing in these pieces, and magical false relations and added notes abound, and everywhere baroque basslines falling step-wise.

But somehow this lack of range doesn't matter. The piano Eclogue (1929, revised two decades later) is one of the most touching, quietly ravishing works of the 20th century. The string miniatures, if limited in scope, are incredibly beautiful contributions to the string orchestra repertoire, with a real feel for the genre and for string writing in general. This again manifests itself in the Traherne setting, Dies Natalis (1939), one of his masterpieces, and one of the finest things written for tenor in English music. The tone painting here is subtle and always completely apt, the ecstatic, soaring phrases alternating with whispered revelations of the gentlest intimacy. And in his finest choral work, the anthem Lo, the Full Final Sacrifice (1946); has there ever been a more hushed and ravishing choral entrance, or a more quietly rapturous amen?

One of the greatest and most sensitive setters of the English word, he had a special affinity for Hardy with whom he felt a keen kinship with with regards to their many shared artistic and humanistic concerns - man's frailty the sense of the transience of life, the awesome beauty and power of nature. The four Hardy song cycles (1922 onwards) make up the back bone of his songs, and are the foundation and basis for everything else in his oeuvre. Not all are as great as the claims that have been made for them, but at their best, they are amongst the finest English songs of the English musical renaissance. Beautiful and deeply moving too are the Shakespeare settings (1942) and the lesser heard pieces for voice and orchestra - the two early Sonnets by Milton (1926) and the finer Farewell to Arms (1925-1944, half early, half late.). Finzi's style changed very little through out his life which meant that works maintained their unity despite often having extremely long gestation periods - often several years or even decades.

What does change is his skill in handling form and being able to construct larger canvases with greater confidence and skill. After the wartime Dies Natalis, the consistency of quality markedly improves, even if he doesn't always completely maintain it. For St.Cecilia (1947) is an impressive work, but ultimately feels a little forced in expression and fails to convince - but that Finzi could force expression at all was a major step for him. The incidental music for Love's Labours Lost (1947) shows this new found versatility to greater effect and is genuinely impressive to the sensitive listener of Finzi's music, even although in global compositional terms it might be dismissed as trivially simple in comparison to what was being conjured up by his contemporaries. The melifluously rhapsodic Clarinet Concerto (1949) has established itself as one of the major concertos for that instrument with its otherwise rather meagre repertoire; this piece points the way to the even finer Cello Concerto (1955). There's a spiffy and rather marvellous Grand Fantasia and Toccata for Piano and Orchestra too, another off cut of the piano concerto from the 1920s but revived and revised in 1953 - The fiercely powerful and improvisatory Fantasia is Finzi's clearest homage to Bach (most notably the chromatic fantasia and fugue) and is otherwise unprecedented in his output.

Intimations of Immortality (1930s -1950), is his largest and most ambitious work - a 45 minute setting for tenor soloist, choir and orchestra of Wordsworth's Ode, a text which had always been considered by common consent and good taste to be "unsettable", an attitude which Finzi dismissed as "bilge and bunkum". And though again it could hardly be said to be an unqualified masterpiece (it has structural problems imposed by the structure of the verse, and Finzi still can't write a proper scherzando passage which sustains its energy, at least not without shamelessly stealing from Walton's Belshazzar's Feast), the work still almost inescapably wills one to attach that word to it. It needs a good performance to bring it off, but certain melting phrases ("A rainbow comes and goes"), and whole portions (such as the epilogue) keep one returning and allow initial scepticisms to fall away and relax into admiration and amazement at the ambition of it and what has been achieved.

The Magnificat (1952) is a decent if ultimately uninspired piece, but finest among the choral works that post date Intimations is the Christmas piece, In Terra Pax (1954), a setting of Bridges. This piece is a perfect gem, and with the cello concerto provide a complete vindication of Finzi's lifelong compositional struggles, his halting successes and failures. The discovery of a universal message in the intensely personal setting, the text and pastoral writing a simultaneous painting of the Shepherd's flocks by night of the bible and a homage to his beloved Cotswalds, the rapt atmosphere the piece evokes, the exquisite details in the vocal and orchestral writing large and small, the agnostic solace found in the religious story, the yearning nostalgia and the visionary glory of the angels' message all make this a beautifully apt summation of his career.

The Cello Concerto (1951-55) in A minor is completely different in mood and tone and suggests things that may have been to come. In 1951 Finzi was diagnosed with Hodgkin's disease, a type of lymphoma, but he continued on as if nothing had happened, and he told few people that his days had been numbered. From the opening orchestral sweep, the first movement is stormily dramatic, fateful, though defiant in tone - a man railing with nature and the cruelty of his predicament; at least, this reading is a tempting one to posit. But it is also celebratory and gloriously beautiful. And here also a confidence and mastery is sustained that has only rarely been achieved before. The slow movement is the crowning glory in a career of ravishing slow movements - so gentle and beautiful that one can't help but be swept away. If one was being really fair, it's a touch too long, and the scherzo that starts within it (a la Rachmaninov piano concerto no.2, as Stephen Banfield points out) as usual climaxes and dies away too soon, but a lovelier movement it would be difficult to imagine. The rondo finale that emerges from the mists is a tuneful romp in the same mode as the finale of the clarinet concerto, and again one is impressed at the assurance in the handling of a fast movement, especially as so much of it was written in a few days, where Finzi might have taken months or years before. The whole thing ends with a darting and mercurial flicker, perhaps a final attempt to flee from death, and then, echoing the three fleeting ascents and hammer blows at the end of the first movement, a final ascent into the ether and maybe a brief glimpse of the beyond, before the final hammer blow. It was the last music Finzi heard, lying in the hospital in late September 1956, and the next morning he was dead.

In all this, his wife Joy has not been mentioned. Theirs was a marriage that was truly happy and loving right to the end. Early on in their relationship, he tried to set any poems he could find with the word joy in them; his final piece of music, composed a month before he died, is a song to a poem by Robert Bridges entitled Since we loved and is a beautifully poignant and fitting tribute to Joy, his life and his art. (Stephen Banfield in his superb biography points out that the penultimate line "All my songs have happy been" is however "glaringly untrue"!)

Though shy and retiring, he was in his small way a modern renaissance man, cultured, immensely well read and extraordinarily inquisitive about almost everything and everyone he came into contact with. He was very interested in up to the minute contemporary music, encouraged many young composers and resurrected the works of many minor English baroque masters (with whom he no doubt felt an affinity with). He set up and conducted the Newbury String Players and was in the best sense an amateur, and proud of it. Suspicious of the young Britten's empty professionalism (a charge perhaps well founded in this composer's lesser early pieces), he saw Vaughan Williams as the greatest British musical figure of the day, and they remained close friends until the end of Finzi's life.

I'm aware that I didn't discuss every single piece from the oeuvre here, but I will go into more detail if anyone ever requests it - the songs and unaccompanied choral works, are perhaps a little ignored here. Maybe another blog post at some point.

ReplyDeleteEnjoyed this Finzi post very much. He doesn't get much love in the United States, alas, which puzzles me greatly. Although some of the smaller choral works show up infrequently, his orchestral works are nowhere to be found.

ReplyDeleteCongratulations on the new blog!